Time really flies when you’re having fun!

This is my second reflection, from when I participated in a Study Visit with a team from Singapore Institute for Mental Health (all of us pictured above). It was co-learning at its finest, where I not learned about quality improvement and healthcare in Jonkoping, but also a great deal about Singapore too!

One of the main reasons that I traveled to Jonkoping was to learn about patients as partners, and patient-led care. This blog post will focus on a few encounters where patients co-produced better care that I witnessed firsthand.

Esther: Before I go further we have to talk about Esther. In Jonkoping, one of the key ingredients to their successes is a flipped perspective when thinking about quality improvement and change. Rather than thinking about, “What’s best for the system? Or what’s best for me, the provider?”, the question always is, “What is best for Esther?” Esther is a hypothetical patient that many of us in healthcare are familiar with. She is a person with a life beyond the walls of the institution, not purely a patient. She is elderly and frail. She has complex health needs. She lives alone. If she lacks effective primary care or transitions from the hospital back to home without support, she does not do well. She’s called a “frequent flyer”. But what about the other elements of her life? What drives her? What motivates her? And most importantly, what matters to her? And how is her problem, our problem (not long term care’s problem or the hospital’s problem – our collective problem!)? How can connections be developed and the system be built so it can respond to the things that matter most to her, beyond simply her medical needs?

While a simple concept, this is sometimes a missing step despite the best of our intentions. It is crucial to not lose sight of patients’ stated needs and preferences because they matter just as much, if not more, to overall health and wellbeing.

Amazingly, the “What is best for Esther” culture is quite visible across Jonkoping region from what I’ve seen. From the clinical microsystem level where decisions are made about how to improve direct patient care environments, all the way to the policy-making level at the government, Esther is kept in mind. For example, programs have been funded by the region because it was the right thing to do for Esther, even when it did not necessarily fall perfectly within the mandated responsibilities of the region. It could have been passed off as “not our problem, it’s someone else’s” but it wasn’t. That’s putting patients at the centre of the team.

As for the clinical examples, here are a few which struck me.

Transitions: One of the most tangible examples of thinking about what matters to patients relates to transitions in care. All patients are asked what matters to them and this turns into an individual care plan, and the system responds to those needs. Think about the last time when you or a loved one was in hospital and needed that extra bit of individualized care. What was it? Someone to look after your dog while you were in the hospital? Why can’t someone do that so you can heal and not be anxious? What about having something nice and comforting painted on the wall of your hospital room? Now don’t get me wrong, there is a place for standards and procedures, or organizations would be incredibly inefficient. But these processes must have laxity and the ability to make exceptions for the patients’ needs, and I see that balance being struck here.

One of the interventions that I’ve noticed are supported discharges where more complicated patients who live alone will have a professional visit them immediately at the time of discharge in their home and help them with the activities that are often overlooked (help with getting groceries, cooking a few meals for the patient, making sure medications are on hand, in addition to getting all the medical equipment set up). These are important factors to an individual’s health and wellness, and matter to them. The healthcare system should not only acknowledge those needs but actively work to support patients needs because that’s what keeps them healthy.

Ward Rounds: During my clinical rotations in Gastroenterology, I always attend morning rounds. A key difference I’ve noticed here is the importance of the patient’s narrative in daily work. Unlike other wards I’ve worked at, in this particular one, the patient is invited every day to come into the room with the team when they are “running the list” (when the team looks at every patient on the ward’s most recent information about their care, reviews their case and new developments, and decides on a plan for that day). Rather than complete this process without the patient as the ward team, instead the patient is included as part of the team. The patient actually sits in the centre of the room and often drives the conversation too. This initiative was driven by the clinical leads in the department in partnership with their patients. The patients contribute their perspectives on what they feel is best for their recovery both inside and outside the hospital and the team can incorporate that into the decision making. Most importantly, it’s not a one-off encounter, but a consistent conversation that shows true partnership with patients.

Self-Dialysis: Brace yourselves, a lot to talk about here.

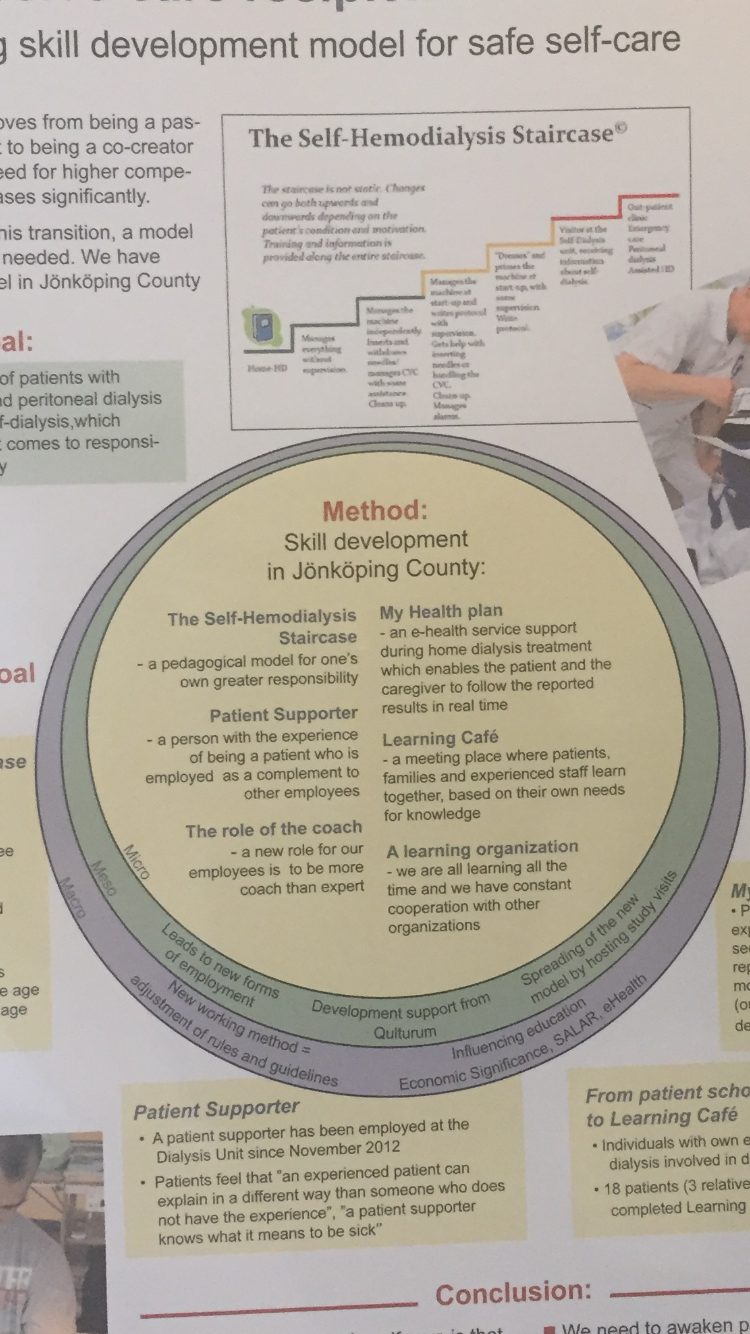

The self-dialysis unit in Jonkoping at the Ryhov hospital is well-known across the world. I had heard of them at The Institute for Healthcare Improvement National Forum this past December where the originators of the unit presented the story behind it to an international audience. You can read more about it here. Or check out this video!

The story behind this program is that a patient undergoing hemodialysis once asked his nurse, “Why can’t I do this myself? Could you teach me? I need control over my life” The nurse responded “How can we start?” and began teaching the patient how to perform their own dialysis under her close supervision. Soon other patients began developing an interest in doing the same thing, and eventually, the unit decided to turn it into a formal program as more and more patients became interested.

The Dialysis Unit itself has multiple streams: peritoneal dialysis, assisted (traditional) hemodialysis, and self-dialysis. Home dialysis is also available too, though many patients express their desire to keep their medical care in the hospital rather than take it home with them. These sentiments have pushed the Self-Dialysis program further and many patients enjoy being able to socialize with other patients and come for hemodialysis when they want to, giving them greater independence over their care, and their life beyond their illness. To date, approximately 60% of the hemodialysis patients are on self-dialysis with a target of 75%.

Nurses staff the unit from 7 AM to 4 PM. Patients who opt for self-dialysis begin their journey on a continuum.

When getting started, patients typically come in during the day and are coached by patient supporters like Patrik Blomqvist, who have been through the unit themselves before. Nurses are also present to coach patients and make sure that their technique is safe and help with any issues or complications. Together in partnership with the patients, they assess their confidence and competence and coach patients towards greater independence in their dialysis. Typically it takes 4-8 weeks for a patient to feel comfortable performing dialysis from start to finish completely on their own but they decide in partnership with the team when the time is right. It is a stepwise progression. Eventually many will complete the entire process themselves, from collecting supplies from the sterile unit, interpreting labs, taking their own blood, documenting their findings, setting up their machines, administering the needles to themselves, participating in exercise while the machine starts up at the onsite gymnasium (many of the patients are awaiting transplant so maintaining fitness is important), and connecting and starting the machine and proceeding with dialysis. They then clean the unit for the next user. The machines themselves have been selected by both the patients and the nursing staff with usability for patients as a critical factor.

Unlike other self-dialysis units, this unit is open to patients 24/7. Patients who become confident and competent in their own dialysis can use their own access cards to come into the unit and dialyze themselves when it is most convenient for them, even without supervision. To do so, they must sign a paper and also must carry a cellphone so they can call for help in case of any emergency. Only 3 patients to date have had to return to assisted hemodialysis due to inability to perform self-dialysis (typically due to cognitive problems that developed such as Alzheimer’s which would have made their ongoing participation unsafe). That being said, there are patients who are in their 80s who are performing their own dialysis. Beyond the immense satisfaction of the patients, clinically, the rate of infections related to dialysis has decreased dramatically.

The story of Ryhov’s self-dialysis unit is an inspiring one. A single patient came forward and suggested a new way of doing things that better met his needs. And rather than being immediately shut down because it seemed so radical and unfathomable, the people working in the system asked, “How can we do this for you?”

And look at what was created. This is patient-centredness at its finest, where patients lead their care, and the system and those who work in it support them in that journey.

Thanks for the opportunity to see all of this (and much more!), Qulturum! It was an inspiration that I will take with me in my future career as a family doctor (happy to say I matched to this career earlier this week!)!

When I eventually interact with patients of my own back in Canada, I wish to take these lessons to heart. As a doctor, I can ask them about what their needs are, and what matters to them, not only for my care, but generally too, and then work to support and coach them as they take more ownership of their health and wellness. I will have an open mind about what is in my toolbox to help my patients, and see my patients as partners who actively participate in care, not passive recipients. This will make me a better doctor. And what’s the point of doing all of this training alongside medical school if I can’t actually use it to work collaboratively with my patients to make the macro and microsystems we live in better?

Now my blogs are a bit behind (just so much to see!), so I’ll be posting about last week’s Microsystem Festival next, followed by a post on my experiences on the wards and primary care clinics of Jonkoping region! There were also a few other site visits that happened during week 2 that I didn’t include to keep this blog more brief (e.g. Mobile Geriatrics Unit, Rehab Clinics) but I’ll place them in the other posts!

Lastly, for the foodies out here, here’s the latest delight from Fika which I have developed an addiction for: Semla! I will certainly be frequenting a certain Swedish bakery back home in Toronto to get my fix when I return.

Till next time! Would love your thoughts and comments!

Ali

Great post on the examples you have seen while there, Ali, and glad that you got to spend time in the Self Dialysis unit that we learned about at IHI this year. We need to have more of this “how can I just make this work” thinking in Canada. As well an acceptance of change and the risk that comes with it. Hoping you can lead this when you get back home!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent example of leading from the heart. Both the patient who asked “why can’t I do this?”, and the nurse who responded, “how can I help you?” demonstrated serious courage and set a great example for the rest of us. I think the framework of progression that incorporates peer mentors and health professionals as coaches is such an interesting dynamic. When we shift our mindset from ‘healthcare providers’ to ‘wellness facilitators’, based on the needs of our patients and families, we create opportunities for better health and improved experience for patients. Thanks for sharing Ali!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] https://qulturum.wordpress.com/2017/03/05/guest-post-ali-damji-canada-snapshots-of-patient-led-care/ […]

LikeLike